OUTLINE | RESEARCH |JOURNAL | MANUSCRIPT

HISTORICAL FICTION: WRITING THE OUTLINE

When I began work on my novel I knew as little about Brazil as the next foreigner. I'd once stopped over at Rio de Janeiro for three days on a flight to Africa, an instant course in cliches of Carnival, samba, beach and jungle. I'd another impression that harked back to my South African childhood, when the country was still tied to England.

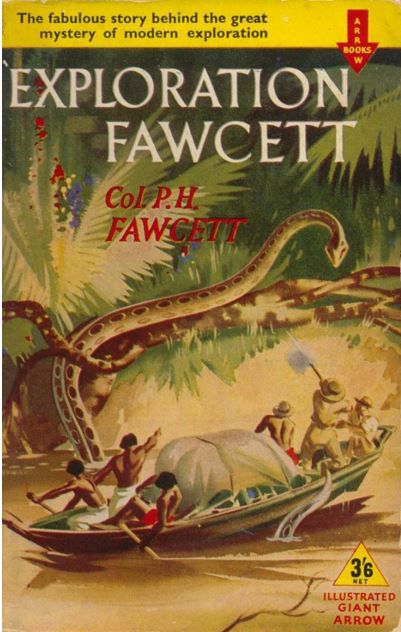

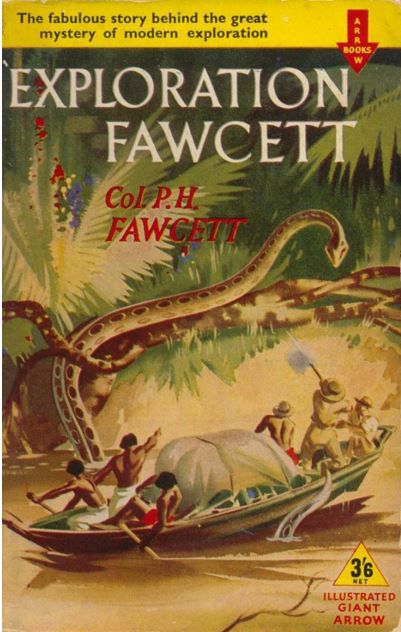

Every month there arrived from London an adventure magazine for boys, its pages filled with the glories of Empire and conquests of its heroes. Among them, explorer Percy Fawcett who was most often depicted in a tiny canoe paddling past the gaping jaws of an anaconda. Colonel Fawcett went in search of a fabulous Lost City in Brazil and vanished forever in Mato Grosso. The intrepid fortune hunter lived on in the imagination of boys Percy Fawcett1ike myself who scoffed at the idea that an Englishman had been killed by headhunters and pictured our champion sitting on a golden throne in El Dorado.

Living in a day when we still saw the world divided into two parts — those who belonged to the British Commonwealth and those who didn't — I naturally considered Fawcett to be the discoverer of the Brazilian interior. Before his time, I believed, no one dared venture there except the denizens of the impenetrable forest.

I remember drawing a huge map of Brazil, days of painstaking work with pen and India ink, with every known river and a myriad tributaries. I marked my hero's route to "Point X" where he disappeared. The map won me a coveted star from my geography teacher, Miss Kane, and a vow to "find" Fawcett. Little did I know that many years later I would visit some of the very places explored by Fawcett that remained as deserted as when he first set eyes on them half a century earlier.

As happens with boyhood fantasies, somewhere along the way I left Fawcett behind and got on with my schooling. Then came the real world and a brief and wretched experience as a law clerk. My adoptive father knew I wanted to be a journalist but warned that before I wasted my life as a writer, I should get a safe "billet," a favorite word of his. He suggested a career in accountancy or better still, a job with the Johannesburg city council, where I would be guaranteed a pension. (A chilling prospect for a seventeen-year-old!) I tried law but after a couple of years of hounding debtors and licking stamps, I abandoned this course.

Then came another round of fantasies with a disastrous attempt to go into business for myself. I founded the Lincoln Swift Organization, an odd mixture of cane furniture factory, pottery distributor, and missing persons bureau. It survived three months. At last, in an act of desperation, I literally threw myself at the feet of the manager of the Johannesburg Star and asked for a job. I got it.

Between daydreams about Fawcett, I'd been writing stories from the age of ten. I was seventeen when I penned my first novel, a three-hundred page saga of teenage angst in a small town in South Africa. Unpublished, I included it with my application to the Star and to my everlasting gratitude, the editors decided to take a chance on me. Three weeks after joining the paper, my name was in print for the first time beneath an article on the editorial page: Happiness is an Unprejudiced Mind.

My career as reporter, features writer and editor spanned seventeen years on three continents. From the Star I went to Post, a newspaper serving the black and mixed-race communities of South Africa. Then to England and the South-East London Mercury, a London weekly; in London I joined Reader's Digest returning to South Africa, where I became editor-in-chief. In 1977, I came to the magazine's headquarters at Pleasantville in the United States. My transfer couldn't have been more propitious.

In 1978 because of my background and the Digest's long-standing relationship with James A. Michener, I was assigned to work with the writer on his South African novel, The Covenant. My two years with Michener convinced me that were I ever to be an author I would have to make a total commitment to writing, not pecking away at a manuscript in the dark of night but out in the open. At the end of 1980, I resigned from the Digest to begin work on Brazil.

Why choose Brazil as my subject? And why on such an immense scale? I've always believed one should make no small dreams for the results will be commensurate. During our time together, Michener and I spoke about places that would lend themselves to treatment in epic novels. He mentioned Alaska and the Caribbean, both of which would become locales for Michener books. I suggested Brazil.

The more I began to think of Brazil, the more reasons I found for wanting to write about the country. My very ignorance prompted question after question, and when I began to look for answers, I quickly sensed a tremendous story that hadn't been told to the North American public. As an outsider to both nations, I had a singular vantage point unbridled with innate prejudices and chauvinism.

Among other compelling reasons for choosing Brazil, not the least was my having just spent two years delving exhaustively into the history of my birthplace. Broadly-speaking, the relations between the races in South Africa and Brazil couldn't have been more different in the 1980s: how, when, why, I wanted to know, did the two nations take such radically different paths? This wasn't something to include in the book I envisaged about Brazil but it gave me a base-line to work from in considering the dynamics of Brazilian society. In Africa, I also traveled widely in Mozambique and Angola, gaining insights into the Portuguese, their history and way of life, a valuable introduction to the colonizers of Brazil.

On January 5, 1981, the first working day of the year, I woke up at the usual time when I would leave for the Digest's offices in Chappaqua. This day there was no Digest, only the vast unknown in Brazil and with my future.

During the next three months I haunted libraries and second-hand bookstores in New York. I wasn't selective but read anything I came across related to Portugal and Brazil, anything but fiction. In plotting so vast a story one has to take care not to lock into the imagination of others and inadvertently borrowing from their works, a pitfall Michener drew my attention to when we were working on The Covenant.

In the back of my original workbook I pasted a letter received from Michener, after I wrote telling him of my decision to quit the Digest.

St. Michaels, MD.,4 October 1980

Dear Errol,

I shall pray.

I note that you wrote to me on the same day that you wrote Thompson, so I judge that between the two letters I have a full picture of your thinking. It's quite gallant, and the most important thing for me to say is that I stand by all I said in your reconstructed note of our December 2 luncheon at Longfellows.* I think this is important because you will need constant assurance in the months ahead:"You unquestionably have the talent to write almost anything you direct your attention to. You are a great researcher, as your copious notes prior to our work sessions together indicated. And you know how to put words together most skillfully as your work on the manuscript proved. With such talents you stand a remarkably good chance in whatever you try. You have also, from what I gleaned in our conversations on the long walks, an acute sense of timeliness in subject matter. That's a rare combination, the most promising I've met with in years of talking with would-be writers."Your tactical problem is clear: husband your savings from Reader's Digest so that you can get through two years of hard work. And get for yourself an advance from a publisher as quickly as possible. I'll support your approach to the publisher if need be, but I would judge that with your record you can make it on your own. And a world of good luck.(*December 2, Longfellow's lunch note: "Every excerpt, every page you have written for my book these past weeks shows that you are a writer with a superb use of the English language, a remarkable vocabulary and a very special turn of phrase. You are as ready to write your book on the black people of South Africa as you will ever be. If you waited five, eight, ten years you'd be no better. Get started tomorrow.

" I never normally go this far, but I would say that you are virtually guaranteed acceptance. Work up the synopsis and write two chapters — they have to be damn good mind you — and you'll definitely get an advance on them. I will give you any help you need in getting it placed with a publisher. I believe this book will be a great success.")

I read hundreds of books and articles on my library forays, not only on my initial three-month plunge into Brazil but as I went along. A small sampling of my reading list includes some of the classic works on Brazil and Portugal, both contemporary and historic:

The Masters and the Slaves, Gilberto Freyre

The Mansions and the Shanties, Gilberto Freyre

Order and Progress, Gilberto Freyre New World in the Tropics, Gilberto Freyre

Bandeirantes and Pioneers, Vianna Moog

History of Portugal, Antonio H. de Oliveira Marques

Portuguese Seaborne Empire, Charles R. Boxer

Portugal and Brazil, Harold Livermore and W.J. Entwhistle

Colonial Background of Modern Brazil, Caio Prado, Jr.

The Brazilians, José Honorio Rodrigues

Latin America, Preston E. James

History of Brazil, Andrew Grant, 1809

History of Brazil, E. Bradford Burns

From Barter to Slavery, Portuguese and Indians, 1500-1800, A. Marchant

Captains of Brazil, Elaine Sanceau

True History of His Captivity, Hans Staden

Discovery of the Amazon, according to account of Fr. Gaspar de Carvajal

The Histories of Brazil, Pero de Magalhaes, trs. John B. Stetson

Hakluyt, the Principal Navigations, Volume XI

A Treatise of Brazil, Padre Fernão de Cardim in Purchas, his Pilgrims XVI

Dutch in Brazil, 1624-1654, Charles R. Boxer

Golden Age of Brazil, 1695-1750 , Charles R. Boxer

Salvador de Sa and the Struggle for Brazil and Angola, Charles R. Boxer

Brazil, Portrait of Half a Continent, T. Lynn Smith

Apostle of Brazil: Padre João Anchieta, Helen G. Dominian

Jews in Colonial Brazil, Arnold Wiznitzer

The Negro in Brazil, Arthur Ramos trs. Richard Pattee

Neither Slave nor Free, David W. Cohen and Jack P. Greene

African Religions of Brazil, Roger Bastide

Brazilian Culture, Fernando de Azevedo, trs. William R. Crawford

Evolution of Brazil, Manoel de Oliveira Lima

Rebellion in the Backlands, Euclides da Cunha

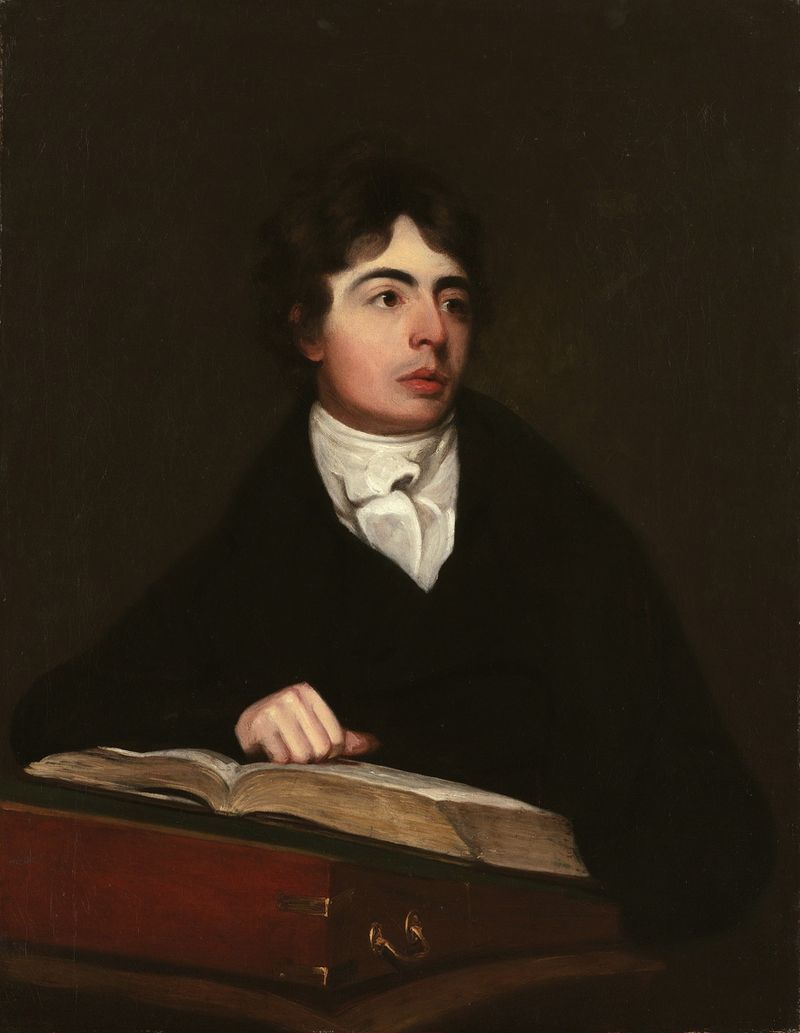

One of my early sources was the three volume History of Brazil written by the English romantic poet, Robert Southey, between 1810 and 1819, considered the first comprehensive history of colonial Brazil. I pored over Southey's thousand-plus pages in awe of his achievement, the closest he ever came to Brazil was among the volumes in the library of his uncle, Reverend Herbert Hill, chaplain to the English Factory at Lisbon. I would have the opportunity to visit Brazil and carried Southey with in my thoughts, an inspiration to another outsider making a literary journey of epic proportions. Southey showed that it could be done.

As I let Brazil seep into my imagination, my first concrete step was to compile a detailed chronology. Alongside this, I mapped out a genealogical timeline for my major families, initially the Cardosas and the da Silvas. I later changed the Cardosas to the "Cavalcantis." As I worked on these timelines, I began to isolate the markers for my characters, the great events where I knew they would have to be present, the sidelines of history where there might be a role for them, as yet undefined and potentially as surprising to me.

The Chronology extends from 8,000 B.C., with north-coast Andes sites of hunter-gatherers to 1981, the year I started my research. So, for example, from 1616 to 1681, the years covering the lifespan of my character, Amador Flôres da Silva, the bandeirante or pathfinder:

1616 Amador Flôres da Silva, born

1616 São Lucas founded/Belém

1618 Ambrósio Fernandes Brandão made first attempt to define or interpret Brazil in Dialogues of the Greatness of Brazil

1621 Simão Cavalcanti, born

1621 Dutch West India Company formed. The 1626-1637 dividends would average between 20 to 50 percent per annum

Creation of the State of Maranhão, after French expelled. (State of Brazil in the south)

Belém had 80 settlers and 50 soldiers

1623 Pedro Cavalcanti, born

1624 Initial capture of Bahia (Salvador) by the Dutch — retaken in 1625 by Luso-Brazilians. (Two more attacks repulsed in 1627)

1627 By now there were 230 sugar mills scattered around the country

Franciscan Friar Vicente do Salvador writes first history of Brazil

1620s Penetration of lower Amazon valley began

1628 Piet Heyn, commanding the Dutch West India company fleet captures entire homeward bound Mexican flota off Havana, without a shot. This ruined Spanish credit in Europe and yielded a 50 percent dividend to Dutch West India Company shareholders and helped finance a vigorous Dutch trade offensive in Brazil

1628-1629 Bernado and Amador da Silva on Bandeira to Guaira region with 69 Paulistas, 900 mamelucos, 2,000 Indians - 7,000 captives - Bernado dies

Bandeirante attacks on missions increase because of the interruption of African slave trade. Major slave raids till 1648; attacks east of Asunción and up São Francisco valley, later into interior

1630 Dutch capture Recife, Pernambuco and begin conquest of northeast Brazil

1637 Count Maurice of Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679), prince of the House of Orange, perhaps the ablest man in Holland at the time appointed governor

1637-1639 First ascent of Amazon led by Pedro Teixiera of Belém, notorious Indian hunter; reversed route of Orellano (1539) and established Portugal's claim to the Amazon basin. 40 large canoes, 70 soldiers, some priests, 1,200 Indians. Founded Tabatinga, farthest westward claim of Portugal. Return trip took from February to December 1639

1639 Pope Urban VIII's severest censures of Church against anyone who enslaved Indians. Riots in Brazil in response.

1641 By 1641, most of the reductions east of the Uruguay River and in Mato Grosso had been decimated by slave hunters from São Paulo. Jesuits forced to withdraw into area now known as the Missiones. After repeated appeals to the Crown, the missionaries were allowed to arm and train their charges who defeated the Bandeirantes in a major fight near Mborore River in 1641. (In 1648, reopening of slave trade reduced reduction raids.)

1644 Amador and Paulista contingent start guerilla operations against Dutch in Pernambuco

By now the Dutch had expanded their conquest until they controlled nearly 1,000 miles of coast from the mouth of the Amazon to the São Francisco River

Amador da Silva marries Varzea Pinto

1637 Count Maurice of Nassau resigns. His policies left a permanent mark on northern Brazil. Some of the Dutch remained to found families like Wanderley, Rollenberg and Lins. Recife had grown from a village of 150 houses to a bustling port with 2,000 buildings.

1648 Alvares Cavalcanti executed; Simão and Pedro exiled to Angola; Henrietta and girls flee to Bahia

Guerilla war had been waged, in one form or another, for fifteen years but Luso-Brazilians now revolt in earnest against the Dutch. (By 1648, Dutch control reduced to Recife and the area surrounding it.)

1649 Monarch elevated Brazil to status of a principality, and thereafter heir to the throne known as Prince of Brazil

Pedro Cavalcanti dies in exile in Angola

1648-1651 First Battle of Guarapes; Brazilian-born whites, blacks, mulattoes and Indians defeat Dutch. Amador with Paulista contingent (April 19)

1650 Second Battle of Guarapes (February 19.)Dutch defeated. Campaign also extended to Angola, where Dutch had gained a foothold, Salvador Correa de Sa e Benavides, Governor of Rio and Capt-General of Angola, sailed from Guanabara Bay with 2,000 men and recaptured Luanda.

1652 Amador on Bandeira with Raposo Tavares, 6,000 miles from São Paulo to Belém via Madeira and Amazon

1652 Olimpio da Silva, born

Simão Cavalcanti marries Maria Escobar

1653 Outbreak of war between the Netherlands and England seals fate of the Dutch in South America. Portuguese fleet blockades Recife and isolates the demoralized Dutch garrison

1654 Trajano da Silva, born

1654 Fr. Antonio Viera's famous sermon on Indian slavery in Maranhão, 1st Sunday in Lent

1654 Simão Cavalcanti marries Leonor da Casal (wife 2)

Fernão Cavalcanti, born

1658 Dutch expelled from Brazil. January 26, (Capitulation of Tarboda,) renouncing all claim to possessions in northeast Brazil. Receive four million cruzados from the Portuguese. (Note: 1664 Dutch ousted from New Amsterdam/New York.)

1658 Domitila Cavalcanti, born

1658 First permanent settlement in Santa Catarina is founded at São Francisco do Sul

1668 - (1666) Two governors of Angola were Brazilians: João Fernandes Viera and André Vidal de Negreiros. Angola was during the 17th and 18th century a province of Brazil. (historian Jaime Cortesão)

1660 Manaus started as a fortress from which sloops (montarias) conveyed cacao, cotton, and turtle oil for street and house lamps to Belém. (date also given as 1669)

1661 England acquires Bombay from Portugal

1664 Minas Gerais first explored by Fernando Dias Paes Leme, though he was not the first European to penetrate it.

1665 King grants permission for first convent in Brazil. (Second not till 70 years later.)

1665 Arosha da Silva, dies

1660s Sugar industry entered decline due to competition from English, French and Dutch in West Indies (1650-1715, Brazil's income from sugar down by two-thirds.)

1669 Guerens Indians kill distinguished citizen of Bahia. Paulistas under João Amaro sent to pacify São Francisco Valley clans

1669 Fort São Jose de Rio Negro built at junction of Negro/Solimoes to become first populated center in Amazon interior

1670 Olimpio da Silva marries Felicidade Bueno

Henrietta Cavalcanti, dies

1671 Paulista known as "The Old Devil" penetrated to one of the affluents of Araguaya River; he cut off the ears of Indian women for the gold nuggets they wore.

1671 Paulista Estévão Ribeiro Parente, at request of governor-general of Bahia took 400 bandeirantes into interior to fight the Indians. Two year "just war" enslaved thousands. Rewarded with sesmarias (plantation.)

1672 Amador, Olimpio, Trajano set out on prospecting Bandeira

1673 Sugar plantations face ruin in competition with West Indies

1674 Bandeira of Fernão Dias Paes Leme, "The Emerald Hunter," lasted for eight years, failed but marked transition from age of bandeiras to that of gold. (=basis for Amador da Silva's story.)

1676 Archbishopric of Brazil created with Salvador as metropolitan see (to remain religious capital of Brazil until 1907.) Two new bishoprics, Rio and Pernambuco, created at same time

1678 Florianopilis founded/gold search

1679 Amador executes his son, Olimpio

1680 Colonia do Sacramento is founded by the Portuguese across the estuary from Buenos Aires, beginning a century and a half of armed rivalry for control of Uruguay and access to the River Plate (ending in 1828, when "Uruguay" emerged.)1681 Amador da Silva, dies

Once the Chronology was complete, I had enough material to flesh out my original plotting ideas in a detailed outline, proposing a saga spanning five centuries and involving multi-generations of two families, the Cavalcantis and the da Silvas whose stories depict the major historical elements in Brazilian society. This ninety-page document comprised an Overview of the novel, Family Trees and the Outline itself. My ideas would constantly evolve during a year of research and travel and throughout the actual writing. There would be many variations in the plot, for I could not know where the characters I created would lead me but the broad plan held firm.

I Prologue

II The Indians

III The Portuguese

IV The Jesuit

V The Bandeirantes

VI The Planters

VII Sons of the Empire

VIII Foreigners and Fanatics

IX The Brazilians

X Carnival

Prologue The Tupiniquin

Book One The Portuguese

Book Two The Jesuit

Book Three The Bandeirantes

Book Four Republicans and Sinners

Book Five Sons of the Empire

Book Six The Brazilians

Epilogue The Candangos

The Pernambucan line of action was a vertical one which effected the regional concentration of effort in the establishment of sugar raising and the sugar industry, the consolidation of a slave holding and agrarian society, and the expulsion of the Dutch, who disturbed this effort and the process of forming an aristocracy. This is in contrast to the activity of the Paulistas or the horizontal mobility of the slave hunters and gold seekers, the founders of the backlands cattle ranches and the missionaries. ( The Mansions and the Shanties, Gilberto Freyre, Alfred A. Knopf, 1966)

Their half-breed progeny became the arch-persecutors of their mother's people. To the supplications of the Jesuits, these case-hardened brigands replied that the Indians had been baptized and were now sure of going to heaven. Worse, they set afoot that poisonous thing, rumor, that the Jesuits had rounded up these forest cattle in order that the slavers might drive them to the killing pens more easily... They used to bring home strings of human ears from Goias as proud exhibits of their prowess in exterminating the Indians. (The Conquest of Brazil, Roy Nash, Barcourt, Brace and Co., 1926)

...and the Jesuit Mola foresaw the onslaught and immediately prepared to receive it by baptizing all those about to be threatened, baptizing them for seven hours until he could no longer raise his arm, and them continuing with someone lifting it for him. Raposo's men sacked the reduction, butchered all who resisted and took 2,000 Indiana into slavery. (The Jesuits, 1534-1921, Thomas Campbell, Encyclopedia Press, 1921.)