ALASKA

Jack Jeffrey

I rode the boxcars in the summers of 1932-35. With the exception of 1935, they were round trips in the West back to Williston, North Dakota.

On July 4, 1935, I left home via the side-door Pullmans to Seattle and then north to Alaska via steamship where I stayed for 25 years.

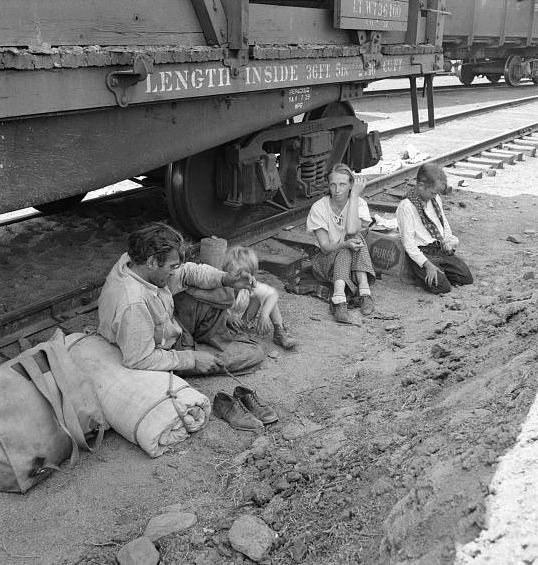

On occasion I see a blurb about riding the rails that doesn't tell the real story. Many was the time we were in a siding going West when an eastbound train passed. Like us, there would be 100 to 150 people aboard, including entire families on the move looking for work.

We were the exception since we were high school kids out on a lark. During the drought and depression years, we could only find work in the harvest fields; thus our travels in June-July to the middle of August.

In 1932, being real short of money we had one heck of a time getting something to eat. Homes close to the railroad yards were hit pretty heavy. We worked for food. We ate from gardens and orchards. After a fast of 24 hours, we even paid 15 cents for a stack of hot cakes and coffee.

I don’t recall if it was 1933 or possibly 1934 when the government set up transient camps in the big cities to help feed and house the thousands of people riding the rails.

They had doctors to check your health upon arrival. Here was a good way to sort out the young kids from the older guys and check for runaways and those wanted by the law.

In Spokane, WA we were run though “the line” and sent to the YMCA uptown across from the Davenport Hotel. We were fed two meals a day and housed in a nice room.

One of the kids on the know (he made money bumming cigarettes from the rich people at the entrance of the Davenport and selling at a discount to the passing working people) told us: “The third morning of your stay at the YMCA should be your last because that’s when they get replies back on inquiries about you.”

We left that morning because we had given false names and a Minot, ND address. I don’t know why. It just seemed like a good idea at the time.

The small villages and towns on the railroad didn’t maintain camps. Some did have offices with a couple ladies who sent you out to work. Upon earning your food, they gave you something like food stamps. You were entitled to a 35 cent meal at any cafe or to receive 35 cents of groceries. One time I remember we built up a supply of groceries that kept us going for five days.

ALASKA

Dave Dawson

“My foot was amputated as the result of a boxcar accident. I was one of lucky ones, because I became rehabilitated.

“I learned that there was no reason you can’t get along with a wooden leg, just as long as you don’t have a wooden head.”

ALABAMA

Charley Bull

Father in show biz = "Lincoln" in movie called "Iron Horse" directed by John Ford, 1924. Saw Hollywood beckoning but failed. "They didn't make a Lincoln picture very often," Charley says wryly.

"Oh, Abraham Lincoln and Ralph Waldo Emerson, what friends you were!"

"All my worldly possessions in a small paper-pressed suitcase."

"Calls them 'tramps'"

"'Vagabonds" from Richard Halliburton

"dollar-a-day work

"20 1/2 when he left California in summer of 1930

"Rode blinds on the Sunset Limited

"Slopped hogs"

"Lit smudgers in citrus groves"

"Worked on a shrimping boat, Gulfport Mississippi"

"Depression? Yes, God knows those were Depression days, but do you know what? Almost no one ever mouthed the threat of anarchy. There were 13 million people unemployed, and some of us had been without a steady job for years, but very few people hated our country, or our government, or our President.

President Roosevelt talked to us from time to time over the radio and we could tell, by the hurt in his voice, that he cared. He held up hope and the promise of a better day, and he implored us -- all of us -- to keep on trying. And we did.

"...I used to attend a meeting now and then of a group that called itself 'technocracy'... 'I'm just in there listening and wearing out some old clothes,' I told a girlfriend, who asked why I went to listen to them.

Charley Bull on hard work:

In Canada, dead of winter, 12-13 hours a day, $6 a month on farm, 14-16 cows milked before breakfast, 5. to 6.30 a.m.; then logging all day and milk again at 6 p.m. Broke ax..."You broke it on purpose, that's what you did," said farmer's wife. Quit. Paid $5.20, with 80 cents deduction for ax.

"So here's how my day went starting in about November of that year -- my senior year in high school in 1929: Wakened by my alarm clock at about 4.30 a.m., made myself a fast breakfast, grabbed my schoolbooks and notebook, walked and trotted about a mile or a little less to my job at the gas station, worked till Hal got there at 8.30, then ran or walked pretty fast to school (about half a mile), worked at the school cafeteria during the noon hour for my mid-day meal. The food was good and here I learned to eat Tamale Pie. Yum, good!

Then after school, I hurried on down to our drug store and went right to work jerking sodas. I'll never forget the wonderful prices we had in those days: cokes -- lemon, cherry or plain coke -- 5 cents; root beer 5 cents, sundaes, ice cream sodas, or milk shakes -- 15 cents, and those splendiferous banana splits, with everything on them, 25 cents.

My regular hours after school were from 4 to 10 p.m., but if it was a rainy night or a slack business night I could leave at 9 p.m. And, oh yes, I got off from 5.30 to 6 p.m. to have dinner. I usually went down the street about a block to the Greeks' where I could get a good meal for 25 cents or 35 cents with dessert. Yeah, man, those were the days! All those good meals for 25 to 35 cents. And, of course, I was making good money or I could never have afforded it. And I had never really expected to be making 35 cents and hour. And I should maybe explain how it happened.

I'd been working there at the drug store about a month when the boss paid me at the end of the week and it was too much money.

"Hi, Mr.........(I just can't remember his name) I think you've given me too much money," I said."No it's not too much Charley. I've given you a raise."I was dumbfounded, I guess. No one had ever given me a raise before that I hadn't asked for. And even then I didn't always get one.

Hal Blackwell, gas station owner... Had a BSc degree in Business Administration... He was just plowed under by the Great Depression. Committed suicide.

"It was a hell of a time. And just a dog-gone shame. And I began to feel a sense of loss, a real personal loss and a sadness for all those folks who had died. Died through no fault of their own. They were just simply killed by the Damned Depression!"

Joined the CCC, the Civilian Conservation Corps. The Three C's, also called Roosevelt's Tree Army, began April 1933. 3,000,000 in 2,600 camps nationwide. Standard pay was $30, of which $25 sent home. A CCC company clerk paid $45.

Most young men saved their money and sent it home. In thousands of cases, it was the only money their families at home were getting.

ALABAMA

Father Roger La Charite

Every time I eat a bologna sandwich, I remember my mother and the hoboes.

When I was growing up during the Depression, many unemployed men would "hop the rails" and travel from town to town, looking desperately for work.

These "knights of the road" would get off the train and come to our home to ask for a bite to eat.

My family lived in a 130-year-old house on a dead-end street. But word had gotten out that people who were down on their luck could get help from my mother.

I remember watching one summer morning as two men trudged up to our back door and knocked timidly. Mother answered the door and listened silently as they stammered out their plea for help.

Even as a child, I could tell that these men were deeply embarrassed by the fact they were jobless and had to beg for food to survive.

Mother always treated such men with respect, no matter how ragged their clothes might be. And although we had little ourselves and my father was often out of work, she never turned anyone away.

These desperate men always left our house with something to eat and drink, even if all we had to offer was a sandwich and a container of cold water.

At that time of the year, the sandwiches were bologna with slices of home grown tomatoes and leaf lettuce from my father's garden.

Sometimes I'd get in on it, too. As a snack she'd make me up a half sandwich with mustard which I'd eat sitting up in the pear tree in our back yard.

In some respects, I'm still carrying on a tradition my parents instilled in me back in the 1930s.

They fed the poor in Vermont as best they could and I'm doing it in Alabama as best I can.

Our Bosco Nutrition Center here in Selma, like my parents' house, is not far from the railroad tracks. My mother would be pleased to see me helping transients looking desperately for work.

But she would have been horrified beyond words to see so many women with small children coming to our door for a bite to eat: Even she might not have been able to stretch bologna and bread as far as we have to.

ALABAMA

Carl Nestle

Born in Cooperstown, NY, 1913

I am 79 years old and I know all about the Depression. When I was 16 I was earning $1.00 an hour. When I turned 17, you couldn’t get a job.

I went three days without food. I shelled corn for 21 cents a bushel. I ate pies with mold on them. I scraped the mold off.

I worked three years for $10 a month and board in the summer months and for nothing in the winter.

ALABAMA

Oliver Emery

My two brothers, sister and I were abandoned by our parents when I was five years of age. Jesse was 10, my sister 8, and my little brother was four. We all were sent to the Kentucky Children's Home.

I rode the rails on and in box cars during the Great Depression of the early thirties.I was on my own at the time; I had walked out on my last foster home at 17.

During my school years, money was very scarce to non existent. I occasionally got menial jobs that paid 75 cents a day. I was desperately trying to get an education; I guess I used every scheme known to man.

Out of the thousands of miles I traveled during those Depression years, there remains one incidents that stands out in my mind that I will never forget.

I was filled with great sadness and disappointment, when I ran upon my father on a boxcar on the L&N railroad.

ALABAMA

Paul G. Meadows

I caught a passenger train in Macon, GA and with one foot and one hand holding the steps of one car and the other hand and foot on another car and rode all the way to Birmingham, ALA in this position. When the train would start off the distance between cars would lengthen until I was in a real stretched out position. Of course, when the train slowed down, the cars would get closer together giving me some relief.

ALABAMA

Braxton Ponder

August 1936, 21, I left Lester, Arkansas to travel the United States.

“I had $4.45 in my pocket to finance the trip. In those days one could buy good cinnamon rolls with raisins for 50 cents a dozen.

I liked cinnamon rolls and figured if I purchased and ate one dozen per day, that would be sufficient food for nine days.

I felt sure I could find a job, work and make some money before the nine days were up.”

“After I left Three Rivers, Texas, I was able to get away from those cinnamon rolls. By being careful, I was able to eat very well most of the time.

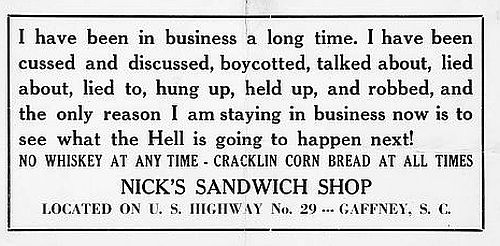

"Eating chili was a big thing in the southwestern states. Some times when money was low, I would go into a cafe and order chili. Crackers were always free. I would keep asking for more crackers and catsup. That way I would make a whole meal of one bowl of chili.

“When we got to Salem, Oregon we realized we were a little too early for the wheat harvest, so we worked a couple of days in the cherry harvest.

"I didn’t like that so I got a job catching rattlesnakes and selling them for coyote bait. Those small desert rattlesnakes, about eighteen inches to two feet long, would come up to the blacktop roads and they would not cross the hot blacktop in the daytime. They would wait until the sun set and then when the road cooled off would cross. We would catch them while they were gathered up along the roadside. The coyote trappers would then buy them.

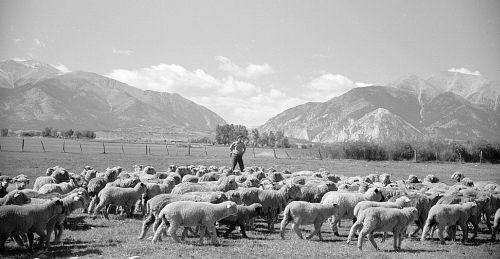

“From Colorado, I went further north to Idaho. Here I got a job for a few days helping bring a flock of sheep down from the summer mountain pasture to a valley for the winter. There were several thousand sheep in the flock. I didn't really know that there were that many sheep in the world.

ALABAMA

Vivian Holland

Widowed mom and I started a restaurant in Henager, Alabama in 1930. I was only 8.

It was hard times and hard work, but the restaurant was successful for many years, It was in a factory and railroad switching area and we fed many, many of the knights of the road free and gave them food to take along the road. They were good people searching for a job and a home. Many of them wrote later and thanked us and a few sent money when they got on their feet again.

The deadbeats during those years at our restaurant were the men who had white collar jobs with oil companies, owned businesses etc and ate on credit at our place and brought their families there to eat, some as much as three meals a day. They ran up debts for food as much as $20 to $40 and then transferred out of town or bankrupted on the bill. That was a lot of food considering that plate lunches with meat and four vegetables with drink and dessert and 2nd helpings for as low as 15c to 25c each.

Many ways of life were so different in those years that some younger people now cannot believe. It made those of us who lived through those times tougher for the hard knocks of life and also more tolerant and sympathetic for those who need us in times of stress. It may have led us to spoil our children because we try to spare them the disappointments we had in growing up. It made us pack rats and collectors because we were forced to save if we had anything and we learned not to waste anything usable.

ALABAMA

William Gordon Golsan

12-15

1930-1933 summers

Left home for adventure and escape unpleasant home conditions. Once was accused of getting girl pregnant which was not true. Rode with uncle looking for work.

Once in railroad yard I spoke to bull and asked if that was good train to get out of town on. He talked awhile, then took me home with him, bought me new shoes and had me spend the night with his family.

Later I was asleep by an outside fire and a man took my shoes. Joe, the only black guy in the group, spotted the man with the shoes, and knocked him out and got my shoes back.

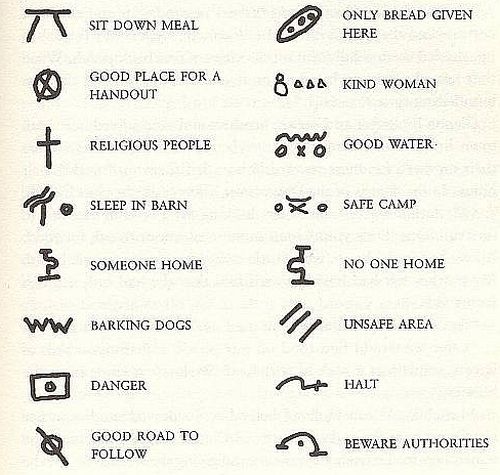

One house had marks on it indicating that the people were generous with hoboes. We stopped, the lady gave us work to do, then served us food. We appreciated her good food and kindness so much that we pitched in and cleaned her yard including flower bed. She came out and was so delighted with our work she invited us back into her kitchen for pie and said, “I love you. I love you Alabama folks!” Her exuberance encouraged us and we cleaned her kitchen for her!

ARKANSAS

Byron Bristol

age 19, 1932

Rode for adventure and hope of finding work in movie studios at Hollywood

One night crossing Kansas to Denver, we were joined by another fellow. A cold black night we struck up an animated conversation about our past lives, family and other things of mutual interest. It was an interesting conversation about things of mutual interest. At dawn I discovered he was black. This was surprising and enlightening for a boy brought up in a white community.

A sight to be remembered: going down Raton Pass at night riding the tender of a steam locomotive pulling a long passenger train. All the cars on the long train were lit up, with the brake shoes and steel wheels throwing sparks!

ARKANSAS

Edward Weber

17-20

1931-1934

The best way to see the country from the top of a boxcar or flat car. Memorable sights:

The Horse Shoe curve on the Pennys.

The Royal Gorge in Colorado on the Denver and Rio Grand Western RR and then across the Utah desert.

The SR out of Bakersfield up the Grapevine. The only railroad I had ever seen where you cross over the same train you are riding.

Inner Tube Johnny wore inner tubes on his feet; when coming to a street curb he would turn around and step up backward.

Scoop Shovel Scottie carried a shovel and played a tune on a lamp post for pennies.

Fruit trains out of CA was fast way to travel. Did not make many stops; the longest was at Carling, Nevada, an icing halt.

ARKANSAS

E.R. Holyfield

I was 12. Having read marvelous “Wild West” magazine stories, I decided I must see that part of our country.

The sum total of 35 cents was my total treasury when I left in 1931.

Left Arkansas hitchhiking but didn’t do too well. Took to the rails. Ended up in Greybull, Wyoming. After six weeks, my parents were really glad to see me.

I lived off the goodwill of people after hitting up their back doors.

ARKANSAS

Howard E. Kemp

The boy I’d partnered with got burned trying to carry the hot stew can up a moving train ladder.”

Disappointment: “Using a government agency once. They treated us like shit. I went one more time with similar results.”

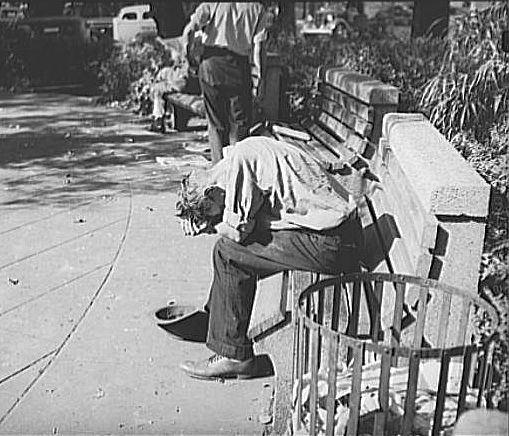

Philosophy: “You become something else on the road, a not there, a not responsible for no one. Drifting is addictive.”

Lessons: "I learned never to mouth off. I learned to go inside myself."

ARKANSAS

Kermit Householder

Thousands of acres of wheat in Kansas, the Texas Panhandle and Oklahoma. From the top of a boxcar with the wheat waving in the wind, it looked like the train was plowing through an ocean.

A railroad bull in Las Vegas locked us in a boxcar in 100 degree heat with no food or water till after dark that night.

ARKANSAS

Robert Marks

1932-33

19

Ran away from CCC, when finance officer refused my request to transfer to woods.

Most remarkable was brakeman who opened up empties for us when we were going over the top of the Rockies. Though it was July, there was snow and it was cold.

The bad were young kids who offered their sisters for a quarter when we entered the yards.

ARKANSAS

Samm Coombs

1938

14, soon to be 15

“The moment we emerged from the tunnel, we both burst into flames. Our ending up among the living had to do with angels, not men. Somehow we managed to beat out each other’s fires."

Had to jump back over train toward caboose…

“At no time and at no place, during war or peace, feast or famine, have I experienced anything that scared me as totally and completely as looking down between those first two cars, at those big steel wheels rolling over that shiny steel track and seeing my almost 15 year old self laying there like a platter of sliced turkey.”

Broke into boxcar and took blankets: By noon the following day we were in jail. The charge? Grand theft! It took a month and a week for them to reduce the charge to simple burglary.

Rode across country to New York City:

“Battery Park was headquarters but I ranged all over 14th Street, Canal Street. A nickel found or bummed could get you a great hot-dog and kraut on a steamy hot bun dripping with spicy mustard."

ARKANSAS

William Glock

“I didn’t have to go bumming around the country like that. I’m a victim of the “wagon’s west” syndrome, and just like to see what’s over there. Wherever.

These were the great days of only 130 million citizens in the U.S. Roads were just that – winding two lanes of in different asphalt. Trains carried all the goods and seemed to run everywhere all the time. The trains were steam and had great individual character. One met fine and interesting people everywhere. Roosevelt was in his White House and all was well with the world.

Diary: June 24 1937 “Got a ride from St. Cloud to Fargo at 2.30 by a couple of communists, one of them argued me into believing communism. Also got a glass of beer, one sandwich, one banana and a sack of nuts from them.”

July 24 1937, San Francisco: Didn’t get up as early as I wanted to. Spent 20 cents downtown for breakfast and hopped a freight train immediately. Got myself into an empty reefer and read stories out of dime novels all the way to Laramie. Ate a couple of meals there and took a boxcar ride to Cheyenne, and had a run-in with a bull. Boy, did he think he was tough. He called himself Denver Slim. Made us unpack our stuff. I went down and took myself a cot and bath at the Snug Harbor flophouse.

July 29, Thursday: Woke up and we were side-tracked at Merriam Junction. Cussed for a while and then cleaned up a little at a water tower. Put on my clean clothes and hiked to the highway. Got a prompt ride. We were on the road through Shakopee, but they took me across to Chaska. Got a ride out of Chaska to Lyndale Ave and then another to downtown. Walked to Hennepin and 6th and ate stew at a restaurant and then to a Turkish Bath and paid 25 cents for the best bath of my life. Also shaved. Went to J.C. Penny and stole a 5 cents white necktie. Then took the street car home."