MISSOURI

Arnold Miller

Many people didn’t think riding the rails was any imposition because many railroad lines across the USA had been given right of way by the government for practically nothing

MISSOURI

Archie Frost

1930-32

17-19

I wrote this poem:

“Don’t grieve for me my bosom friend

For I’ve listened to the wind

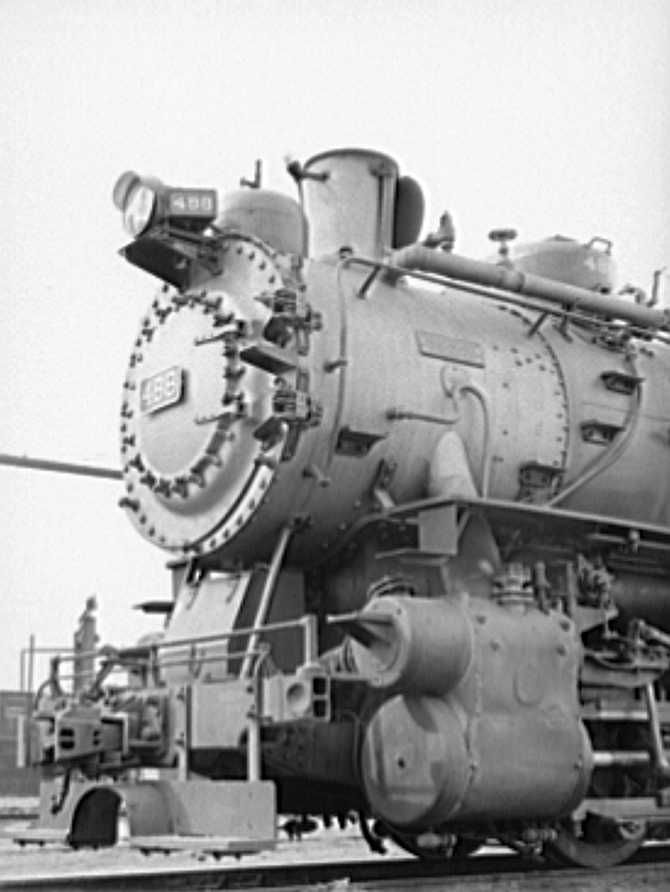

I’ve rode the rails of the old SP

While the Lord above looked after me

I’ve looked down from the mountains high

And heard the screaming eagles cry

I’ve searched for gold and hunted bear

Blow down the canyon in the night

And chose the shadows in their flight

I think I’ve been most everywhere.”

MISSOURI

Doyle Yancey

18-21

1934-38

Before radios were very numerous and no TV people received only limited knowledge of national news of reliable accuracy.

Riding the rails gave me much knowledge of the abuses in our system. Failure to administer equal justice. What not to expect from our legal system. Politics – how they actually perform. Getting to know and live with people of different racial and ethnic background.

Hobo jargon:

dingbat: older person, a tramp

chuck sack: sack tied at corners with rope and hung over shoulders

dummy loaf or part of: bread stored in chuck sack with beans, bacon, rice etc.

dummy up: fall silent (of speech.)

hit the grit: jump off train in motion to escape bulls.

nickel up: offering small change at bakeries, butchers

cook up: jungle cooking.

boil up can: round or square 4-5 gallon can for cooking

telescope: several cans fitted inside each other for jungle cooking/utensils.

floater: suspended sentence, usually on vagrant charge.

MISSOURI

Elroy Thornhall

I was born into extreme poverty on 11/29/25 and never remembered having anything to eat or decent shoes on my feet for school. I remember Dad wrapping Gunny sacks on my feet (burlap) so I could walk to school in the snow.

Mom and Dad never seemed to get along and were always separating and finally divorced when I was 10 years old.

Neither could feed or make a home for me so I was confined to a mental home in Fulton MO as there was no where else to go. Since I was not mentally ill they could not keep me so I was released and went to the Salvation Army in Jefferson City, where my mother and I lived and she worked among other homeless people for our food, clothing and a place to sleep.

My mother died when I was 13, and that seemed to be the final blow for me. I finally achieved an 8th grade education after attending a total of 25 schools. I graduated from a one room school in Cool Springs, St. Charles Co. with 7 students from the 1st grade through the 8th.

This is where my education really begins. I worked the harvest fields and farms all over the Midwest, traveling mostly by hitching rides on the highway, as I found the highway more friendly and cars warmer than the boxcars. I had to lie many times about my age when I was asked to drive or enter a bar.

Any old barn was a warm haven at night from the cold, and hay or straw was a fine bed. Many times I got caught away from nowhere and had to sleep on the ground, and woke up with frost all over me.

I would travel in any direction I could to get a ride, as direction or distance, or location had no meaning. I chose to work for food and hand-me-down clothes, but that wasn’t always possible, so sometimes I was forced to steal. I meant no one any harm but I played the hand I was dealt.

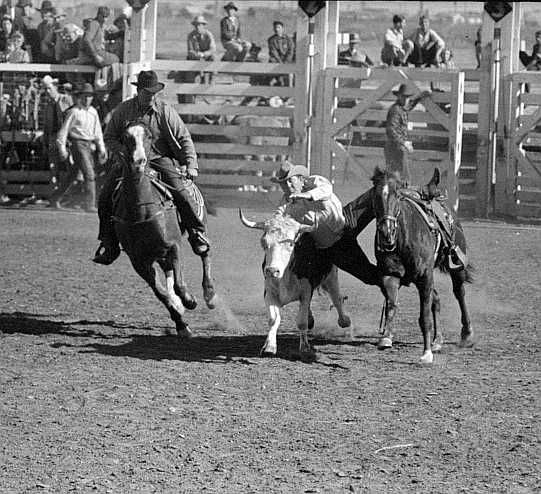

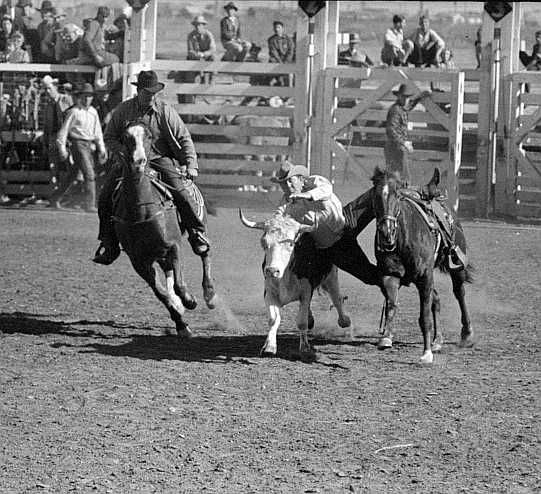

I joined a traveling rodeo when I was 15 and rode broncos and bulls for three meals and a bed.

By the time I was 17 there wasn’t much I couldn’t do but the same old problem persisted. No work, no money, too young, no high school diploma, no friends and no family.

Then all hell broke loose and the picture changed. On Dec 7, 1941 Japan bombed Pearl harbor. The next five years were a completely new story for me. A very disastrous and heart wrenching part of my life..

I was married in 1948 and am still married to the same woman, with 4 children and 13 grandchildren, 4 great grandchildren. I am a self-made man and during my marriage became self-educated and retired as an engineer. After retirement I became a songwriter.

MISSOURI

Fred Griffin

A fellow and I rode the Mo Pac Railroad out of Kansas City to the wheat harvest. There was so many men, it looked like black birds on top of the cars.

We rode the Mo Pac out of Sheffield going to Independence, Kansas. It was raining. There was only one box car that had rods under it. We sat on the rods and rode through the storm. (The old box cars had iron rods from one end of car to the other end of the car.)

A thrill walking along tops of twenty boxcars after dark with train running at 35 mph. Jump from one car to another.

I am 87 years old and every time I see a freight train, I would like to catch it.

MISSOURI

George Phillips

11 to 17

1926-1932

For adventure initially, but 1932 trip for work “bumming” the Oregon trail

“There is no other feeling in the world like sitting in the doorway of a side car Pullman and watching the world go by, listening to the clickety clack of wheels on track, seeing all new country spread out, something new every step of the way…."

So we clattered along listening to that old steam whistle blowing for crossings and towns. After a while it got too dark to see anything but the lights along the way. We could see the lights of farmhouses and imagine those lucky people sitting down to supper, when all we had was some dry doughnuts, but as for myself it was no big deal ‘cause I was going somewhere. Wanderlust really had me.

“The so-called Great Depression meant nothing to me. I had never known anything better.”

“Before we left. I made a trip home to pick up some clothes and stuff and say goodbye to Dad and Alma and my sisters, Caroline and Daisy Lee. I think my sisters were the only ones who cared to see me go.

Dad didn’t say much. His parting words were “Try and be a Man.” I think he understood because he was always looking over the next hill too.

In those days there were many bums, hobos, tramps, people out of work and people trying to get out of work.

I fell from a train at Wreath, Ore and was knocked unconscious for some time. I never rode another freight.

One of my older brothers fell from a train near Condon, Oregon, lost a leg and a short time later his life.

Stop? I fell in love with an area and a girl at the same time. It took eight or nine years and a war to get over it.

James Blackman

1935 - 1938, 18-21

We lived in the Ozarks. My family was very poor. There was no future for young people.

It was easy to survive during the thirties. It was a time of helping and trusting people. I don’t believe I was ever turned down, when I asked for food.

I remember one time in Dallas, I knocked on a back door and asked a lady for food. She was beautiful, about 35, and real well dressed. At first she started to turn me down, then she said, Come on in.” The table was set with fine food, flowers, and all. Her husband had just called and said he had to work late. No hanky panky, just a fine lady and a good meal.

In Cincinnati another guy and I were sitting by the track near the Ohio river, waiting for a south bound freight. A railroad dick came by and asked us if we were going south. We told him yes. He told us not to catch the first one as it was a manifest, but to catch second freight. We walked on down to the river. When the first freight pulled out we caught it and the dick saw us. About 200 yards down the track, he pulled his pistol and fired several shots at us. Luck was with us. Neither was hit.

In 1940 I joined the marine corps, was a paratrooper. Fought on both Guadalcanal and Iwo Jima. Received purple heart and bronze star.

MISSOURI

Ulan Miller

“Lyle and I got off at a railroad yard in Des Moines, Iowa. We were headed for Albert Lea, Minn, where we had word that there was work in the truck farms and also could be work in shocking wheat or oats, as they did in those days. As we found the railroad yards were pretty large we made out toward the residential part of the town.

We went to house and knocked on the door. A lady came to the door and we asked for something to eat. She said "Wait a minute." She was gone several minutes and finally came to the door and handed out to us two very dry slices of bread.

“Now, boys, I’m not giving you this for your sakes, or my sake, but I’m giving it to you for the Lord’s sake.”

Lyle took the bread and forlorn looking in his way, said “Lady, please for the Lord’s sake would you go back and put a little butter or jam on it.. . huh?”

MISSOURI

Robert Keerns

age 15, 1936

Large train of empty boxcars was sidetracked and left in open country west of Big Spring, Texas. Over 300 Bums were stranded and left for days without food or water. Many of us walked across country to a highway and hence back to Big Springs. Some of those bums may be there yet.

Stop? Wound up with 5 cents and enough Bull Durham to roll one cigarette, and decided it was time to go home. Took a good beating when I got there but decided school wasn’t such a bad place after all.

MISSOURI

Ted Wilson

On top of boxcars is a walkway made up of three boards each about 5 ½ inches wide with about an inch or two between running the length of the car. Tied ourselves on with belt. When we went to sleep, we just hoped belt wouldn’t break.

MISSISSIPPI

Charlie Jordan

Rode the rails for about six months, when he was in CCC in Emmett, Idaho.

In 1941, I enlisted in the army. I was sent to the Philippines in April 1941 and after the Bataan and Corrigidor surrender, I was a Japanese POW for 40 ½ months, 30 of which I spent in Japan working in coal mines.

Those tough Depression years gave me the strength to live and survive.

MISSISSIPPI

Giles Wilkins

b 1912

“I am an ole country boy raised by the railroad tracks in the middle of Mississippi.”

The year was 1931 just out of high school, no job and none in sight. I, my brother and a cousin said we will go out to Texas and pick cotton.

I finished high school in 1931 at which time you couldn’t get 50c for plowing a mule all day. It was useless to ask for a job and I felt I was a burden on my family.”

We went into Plainview Texas and the detectives were running us out of the yards. After it was over one boy said if you don’t believe he kicked my behind, look at this can of Prince Albert smoking tobacco that was in his back pocket. It was flat as a dime.

One old dude said, Son you don’t ever have to go hungry. He said when he got off the train, he looked through the garbage cans and found him a slice of bread. He picked him out a nice house and went to it. He put the bread down in the yard by the steps. He then rang the door bell. When some one came out he asked if he could have that slice of bread he was so hungry. He said if it was a woman it worked every time.

There were lots of funny things out there. I told some of the boys when I got home I got so hungry I licked the sweat off a café window. It was a wonderful experience.

On a Sunday way down in the State of Texas, I went to a nice house and a nice man came to the door. I told him I was hungry. He said my table is full up, but some one will get up and we will let you eat to you stomach is full. All his kin people including Grandad started asking me questions. I was really embarrassed but I was really full.

Later on I hired out and worked 30 years on a railroad as an engine foreman. I always had a soft spot in my heart when I ran across a bo. I would tell them which boxcar to board.

MONTANA

Alvin Svalstad

Mostly hitch-hiking but nice details of trip to Chicago World’s Fair, exemplifying lure it had for all. Rode rails on last leg of return trip.

1933, left Sisseton, South Dakota, where he was a teacher.

“You have such a bad heart that if you go to the fair you will come back in a box.”

I stepped out of the office door, looked east and west. And decided that, if I was to go in a box, I could as well do it now so I headed east toward Chicago.

Madison, Wisconsin. “The Transient Home was an old building that had been a livery barn. When I entered I could smell the odor of horses past. The lower floor was empty except for an old desk over which hung a fly specked light bulb from a drop cord. Behind the desk sat a sallow faced man who looked as if he had come from a prison. I told him I needed a place to sleep. “OK, but you have to leave any money or valuables here.”

I lied and said I had no money or valuables. I wouldn’t have trusted him with a penny to say nothing of the eleven dollars and twenty five cents I had in my billfold. He took me to a stack of army blankets, handed me two and led me up some stairs to the loft. The loft must have had over a hundred army cost nearly all occupied. He showed me an empty cot and I threw my blankets on it.

I stopped to look around me. There on the cot to my right a white man with a scar on his face that gave him a perpetual leer. He spoke with a sneer: "Wise guy what’s in that case of yours?

The sound of his voice and the sweaty odor of all those bodies made me think twice and I grabbed my suitcase and retreated down the steps and into the street. I decided 40 cents was little to pay for a clean room and privacy at the YMCA.

A big limousine offered me a ride. There were two ladies in the front seat and a young fellow in the back seat. I crawled in the back and off we went. The four of us had a lively conversation. They had plenty money and enjoyed hearing me tell them about leaving home with only $15 in my pocket. When we came to Wisconsin Dells they had to leave the highway.

One lady asked how much money I had left and I said $2.50. She said Here is 50 cents to pay for another night. I told her I could make it on what I had. She insisted and finally said, You take this fifty cents and when you get home and have money pass it on to some other needy person. I took the money. You can’t imagine how many times I have passed on that 50c.

MONTANA

Harry Rose

I was born in Ohio on April l, 1912. Growing up, I had always wanted to go to Montana where I had an aunt and uncle. So on the 28th of June 1934, I started on my way hitch hiking to Montana. I left home with the milkman, Louis Strait. All I had was a cardboard suitcase, a comb, a change of clothes and $18.50 in my pocket.

Often I started out early in the morning and, if I was lucky, would get a ride with a trucker and would ride all night. In those days it was easy to get a ride, if you were clean. You could get a shave and haircut for 40c and I always tried to stay clean. While riding with the truckers, I would help load freight, change tires, or anything else that needed to be done on the trucks. I stopped off one night and got a room in Iowa for $1 in a hotel that had 10 cents.

dance girls and a bar. It was fun there. I had $14 left, so before I went to bed. I had the hotel keeper lock my money in the safe.

When I got to Big Timber, Montana in July with $5 left in my pocket, I talked to the sheriff and also had a glass of beer with him. He said he would let me sleep in the jail for a week. With a grin, he said he would leave the door unlocked.

It turned out that I had mistakenly gone to Big Timber instead of Bigfork where my relatives actually lived. In a few days, I got a job baling hay for the government at 40 cents per hour, ten hours a day. It was hot, hard work but I needed a job. I found a room for $2.50 a week and boarded at a cafe for $8.50 per week. What meals: Plenty of everything and very good.

I spent seven months in the Big Timber area and then finally got in contact with my relatives in Bigfork. I remember it was Washington's Birthday when I headed up toward northwest Montana. I arrived there early March 1935.

I met my Norwegian wife, Marion, in Bigfork and we were married June 28, 1936. Now it has been 56 years and we're still together.

MONTANA

Irv and Glen Landes

(Sister shared their written memories.)

Irv tells of almost freezing to death riding across the mountains on an open lumber car. About 40 years later, a fellow came up to Irv and told him that Irv had saved his life that day. He didn’t have cash to buy a ticket and Irv had loaned him the money for a ticket.”

In the fall of 34, we decided we would take a train for Wenatchee, WA and take in the apple harvest.

We each had five dollars. At Williston, we climbed into an empty box car, settled down at one end with our bedroll. A bull shot a flashlight at us…”You little SOBS get the hell out of there."

We got out wondering what next, when we noticed a bum beckoning us toward him. He told us he would tell us when to get on, finally we were rolling on. We managed to grab some candy bars at Havre, Montana, got into a lineup at a soup kitchen, perhaps a couple of hundred men and some “almost men” received a bowl of soup.

Spokane, WA: We had a hard time trying to catch a freight. Had to hang around a water tank for couple of days.

One group had snared a couple of gophers, asked at several homes for some vegetables and made stew in a syrup pail, finally a freight stopped. It was here that we helped a man with one leg on, one leg was off at the knee and bleeding.

From Spokane we made it to Wenatchee. One morning on way I woke up and there were about 30 guys in the one boxcar. There were times when it was fun, riding in a boxcar doorway, legs dangling out, watching trout leap in mountain steams, couple of times train stopped to meet another, we would jump out and pick wild strawberries.

At Sunny Slope Apple Farm, I saved 200 dollars that fall, our goal was 100 boxes per day but never made it. We received 4 1/2 cents per 40 pound heaped up box.

On our way home, arrived at Whitefish, Montana, riding in an open lumber car - 8 degree and snowing. We were so cold we had to help each other off. We bought tickets to Williston and rode in style. I remember the passengers giving us strange glances. I am sure we slept the entire distance home.

MONTANA

Clarence A."Pinky" Bourne

Retired Chief of Police, Ronan, Montana, born 1915

Spring 1933, with good friend Elmer "Speed" Silloway

Runaways for Adventure.

Young biker fanatics. Wanted to visit Harley Davidson Motorcycle factory in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Plus World's Fair, Chicago and "Sally Rand."

Left Great Falls, Montana railroad yards aboard Great Northern freight train bound for Billings, Montana at midnight. Left with $7 altogether.

Riding the tops, got caught in a "gully washer," a prairie monsoon. Speed's jacket whipped away in a gust of wind, Pinky's cardboard suitcase ruined.

A big percentage or riders were WWI veterans, Bonus Army veterans. -- There was a large gathering of Bo's at El Reno, Oklahoma. It was on a main transcontinental line. The jungle was crowded.

The WWI soldiers had just received their bonus. They were filthy rich. We saw one blanket piled high with 5's, 10's, 20's, and not a few C notes. To a couple of boys with nothing in their pockets but holes, it was a devastating sight. There could easily have been five to ten thousand bucks in that small area. Most of the gambling was done around this blanket.

These guys were the first of the big time spenders. They bet them high..... They sent a couple of Bo's to town with some green in their paws. Soon they returned with what we thought to be two big ham bolognas. The packages were about four inches in diameter and about 16 inches long, wrapped in white butcher's paper. When they cracked them open each contained six or eight large cans of sterno canned heat. No hog wash 3.2% beer for these guys. We found it prudent to leave at this time.

At El Reno, we met a Bo with what he called a "poker knife." It looked like an ordinary pocket knife, but had a "D" ring on one end, not unlike a Boy Scout knife. You couldn't open the blade unless you knew the trick, which he showed us. While we were watching, he bet a couple of bo's a buck a throw that they couldn't open it, and of course they lost their buck. Then he would bet them another buck that either one of these boys could open it, and they lost another buck. Then he confided in us that he was going to catch a real big sucker.

He says, "I only got a few bucks and if you boys want to double your bank roll, you can put it with mine." We did. All three bucks. Everything went as planned up to where one of us was to open the knife. Try as hard as we could, we could not open it. We felt real bad for being the reason the poor feller lost all of his money, to say nothing of ours. When we had time to think it over, we figured the two men were partners and had switched knives on us.

Blinds: Passenger coaches have a kind of half vestibule on each end. When two are hooked together, they form a complete vestibule. The front coach has no coach to connect to and the coal tender has no such appendage. This half open air vestibule is called the blinds.

When catching a ride on a moving train, if it isn't moving too fast and there is an open door on an empty car, you run along beside it, reach up and grasp the hasp that's hanging down, then swing up into the car. If you don't make it for some reason, you will just, in all probability, slide and roll along in the cinders.

When you catch a train that has no empties, you run alongside as fast as you can, grab a rung on the ladder on the front side of the box car. If you have a strong grip, the momentum will jerk you up onto the ladder, like a plane being shot out of a catapult on a carrier. If the run is jerked out of your hand, chances are that you will just bounce off the side of the box car.

If you grabbed a rung on the side at the rear of the car and lost it, you could have been slammed around behind the car and possibly fallen on the tracks where you would've been bisected.

We didn't hit Cheyenne, Wyo, but other Bo's warned us to stay clear of there. The Railroad bull carried a bull whip and was proficient in its use.

At Chicago, they had all the Deputy Sheriffs in the world there. As soon as we would alight from our private car, they would bodily bounce us back on, not too gentle either. After one go-round in one side, and two on the other, we decided that Sally Rand didn't really mean that much to us.

MONTANA

Ralph Shirley

1936

Two green kids from Glen Ullen, ND. Coal mining town

“The lure of the real world beckoned.”

Both excited and scared.

Better than hitch-hiking: At night you have a place to sleep and ride.

Going east was usually easier than going the other way. Empty auto boxes and paper.

When I first traveled through Billings, Montana, it was love at first sight for me. There were the beautiful Beartooth Mountains off to the southwest. The area was an irrigated green land while a part of western North Dakota was turning to a desert.

There were places where a person could walk on sand and be over the top of a three wire fence. What was not sand on the ground was topsoil floating overhead in dust storms.

The professional hobos I knew were usually solitary stoic individuals. They had mostly given up on life itself. They would stare at one spot for a long period of time. Occasionally they would shift their eyes to catch something of interest.

I have noticed the same kinds of expressions of men who have seen too much combat. These men recognized one another, but were not particularly friendly to their own kind.

They would cooperate in the jungle with food, one would put in some carrots he had bagged or stolen, another would supply cabbage or any other vegetable. Some would contribute meat. This was all thrown into a stew pot or five gallon can. It was stirred and boiled. These men always seemed to be unshaven with deep wrinkled faces. Some were handicapped by the loss of fingers or arms. Some lost toes and many had facial battle scars.

The exception to being stoic and solitary was when they had access to cheap wine, rot gut liquor or anything with a high alcohol content. It was then that many of the knifings, fights and even killings occurred.

I was a kid of 17 at the time and felt pretty comfortable with these fellows, part of it was because I felt more alert and stronger than most of them. Then too there was a certain attraction to these different and pathetic individuals. Because of my youth they would talk to me before their own. Usually they would talk down to me and impart some information.

Milwaukee Red said, "Kid this is not the life for you but it you ever get on the Santa Fe watch out for that Bull at. . . . He is a tough son-of-a-bitch." Then he went on to spill out a long tale of his experiences on the Santa Fe. I thanked him and he smiled. The names he mentioned might have been points on the moon for all I knew. Still it seemed exotic and exciting.

As an adult looking back this nomadic life had to be monotonous. All railroad tracks look the same. All steam engines sound the same. No hobo was allowed to get too far from the railroad tracks. It is no wonder they didn't care which direction they were going.

My mind compares this to an airline pilot in this respect only, the tops of clouds look the same the world over. With our shrinking world the airports must begin to seem strikingly similar also.

At this late date it seems highly improbable that any of the men I knew are still alive. How can the human body, stand irregular food and sleep, hot and cold, jiggling and bouncing, stress, poor and irregular personal habits, rot-gut whiskey and many more negative things?

This generation may ask, "Why didn't you hitchhike?" Well many of us did but it was mostly for shorter distances. It was hard to hitchhike at night so that meant you had to get a hotel room or sleep in the open. With the train you could roll all night and be a lot farther down the road. Then, too, on the rails there was only one owner -- in some respects it was like dealing with the government.

While hitchhiking some farmer might not appreciate your sleeping in his corn field. When hitchhiking you are alone. You take chances with the person you ride with. You are observed by the law. On the railroad you are all part of a small army. It seems to come down to traveling the greater distance for the least amount of money on the rails.

Now I can tell you about emerging from a railroad tunnel with cinders down my neck and thankful to be breathing. There was a day without food because I didn't want to get off the train. There was the time it was necessary to strap myself to the car with my belt to keep from rolling off. There was the sight of a five acre area jammed full of travelers. There was the little fires, the smoke, the noise, and long lines of people waiting for a turn at spring water running from a pipe. These were not necessarily the best of times.

MONTANA

Ray Volkman

I was a junior in high school and my brother was six years older. Spent part of one summer riding the rails.

We left Great Falls, MT and made our fist mistake getting in a gondola right behind the steam engine. When it took off the cinders came down on our heads and all over us. It felt like we had caps on, the cinders was so solid in our hair.

Used two belts to tie himself to catwalk.

My brother had a crippled arm. So he had to carry his pack in the crook of his arm and climb with his one hand. I stayed right behind him so that if he fell I could catch him.