We stepped away from our typewriters with the idea of taking a break but they followed us out between the loblolly pines, Nongqause and Mhlakaza and witnesses to their danse macabre. Men like dashing Major Richard Saltwood, one of the main protagonists of The Englishmen. Well bred, courageous, Richard was the quintessential officer and gentleman, who served six campaigns in India before immigrating to the Cape Colony in 1820, four decades before the cattle killing. The major did everything in his power to stop the madness and when the dying began, he led the relief effort to save the Xhosa, his enemy in three bloody frontier wars.

I knew Richard Saltwood and his three brothers intimately, for I plotted many of their exploits, when Michener and I were putting our heads together to people The Covenant. The Saltwoods hailed from the ancient bishopric of Old Sarum near Salisbury, where their ancestor Nicholas Saltwood, captain of the Acorn, put down roots after making a fortune on a voyage to the Spice Islands in the seventeenth century. Peter, oldest of Richard's brothers, was a respected Member of Parliament, despite holding the seat of Sarum, "rottenest of the rotten boroughs," where voters were as invisible as ghost-warriors of the Xhosa. David, youngest of the Saltwoods, was a rebel who turned his back on John Bull and went to America founding a branch of the family. Hilary was four years older than Richard and reached the Cape a decade before him, a godly son of England serving the London Missionary Society. He was a darling of the Hottentots and ardent defender of the Xhosa against depredations by Dutch Boers. Reverend Saltwood's path was studded with thorns that lacerated and finally killed him and his wife Emma, a Madagascan convert with whom Hilary found sweet redemption.

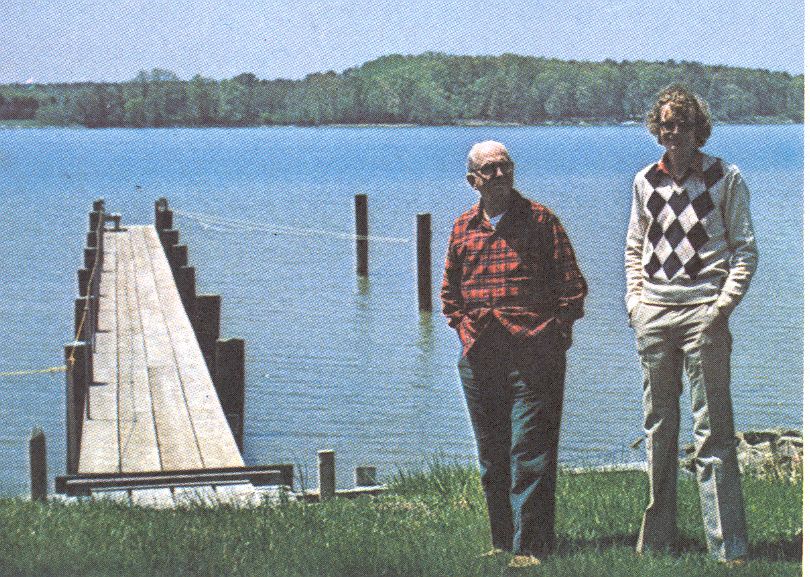

On our walks, Michener often chided me for incessant chatter. "You're not getting any benefit, all this talking while you walk. You're not putting air into your lungs." Jim pumped up his long stride and surged forward. He never stopped me talking and I never held back for I knew we'd a vast and empty veld to populate.

Never once did I say, 'So now we have this Englishman at the mission station in 1819. How does he get to the Orange River?' without Uys having nine or eleven possibilities, all good, all logical, all beautifully coordinated. Often I would say, 'too complicated for our boy,' or 'I doubt our boy would go so far,' but just as often I would say, 'That might be just what he'd do.'

He showed such a mastery of and predilection for plotting that again and again he came up with dazzling ideas which immediately attracted my attention. I am no good at plotting, hold it to be almost an excrescence, and pay far too little attention to it, so that Uys's bold suggestions were often appreciated. I judge that he could plot six novels a year with intricate beauties; he should've been in G-2 in some complicated war situation. — James A. Michener, aide-memoire, 16 April 1979

Even I couldn't have dreamed up the circumstances that saw me on that Maryland road in 1979 or the coincidences that drew Michener and I together. Jim was a very private person, who was happy to parade a cast of thousands in front of the world but kept his own universe under wraps. I, by contrast, was known to stay up until the cows came home gabbing with anyone who would hear my stories or share their own adventures. I could never see Michener in one of the smoky dens on Cape Town's waterfront or a Johannesburg dive like my uncle Henry's "Rendezvous." Of course, more than three decades earlier, Jim sat for hours with the Quinn's Bar gang on Tahiti and at Aggie Grey's, where the goddesses of the South Seas danced siva-siva and nights were enchanted.

There were no juke joints on Broad Creek and besides I was there to wrestle with big ideas, not sit gossiping with one of the great minds of America. Still, there were times when the talk turned to two characters only, ourselves. On my first visit to St. Michaels in May 1978, I told Michener how I happened to bear the name of a proud Afrikaner family, having been adopted as a baby.

"I was adopted," Jim said.

"I never knew my birth parents."

Nor did he, said Jim. Mabel Michener, a widow, took him in. There was no man in the house.

"When I was six, Uys left my mother. I wasn't told I was adopted until I was twelve. I'd had some idea, nothing specific, just a feeling I wasn't Joey Uys's child."

"How did you find out?"

"My mother and I fought like cat and dog. One day she screamed at me. 'You're not my son. You're trash picked up in the gutter.' I told her I knew I was adopted. That made her angrier. 'Who told you?' No one, I said. I just knew."

Jim told me about a member of the Michener clan, who started sending him letters after he began to win recognition. Jim wasn't a real Michener, the anonymous writer said, but a bastard and a disgrace unfit to bear the name. Year after year, the letters kept coming, their poison more and more vitriolic. Every advance Jim made, there'd be a missive filled with rage and vituperation.

"I've not the slightest idea who he is." Jim had a notion that the writer was a man. Where were the letters from? I asked. Philadelphia, but that meant little to Jim. One thing that his detractor wrote rang true for him: "'Just who the hell do you think you are, trying to be better than you are?'"

"He got that right," Jim said. "I've always tried to be better than I was."

Dark and dismal memories for Michener and me but there were happier recollections of two boys growing up decades and continents apart yet remarkably alike. Our mothers both lived from hand to mouth, with never a penny to spare. At nine, Jim was scouring the Doylestown woods for chestnuts to sell to neighbors; my first enterprise was selling peaches in the street outside our house when I was six. From the age of eleven until he was a young man, Jim worked at many jobs from paper carrier to ticket taker at the famous Willow Grove amusement park outside Philadelphia.

I was eleven when I started a mini-career as salesman in a Johannesburg toy store, hawking hula-hoops on Eloff Street. Every year I joined the pitchmen at the Rand Easter Show, the country's premier exposition, pushing anything from teddy bears to "miracle" bottle openers. As teenagers, Michener and I both hit the road and stuck out our thumbs hitchhiking thousands of miles around our countries, beginning the journeys that would see us walking together that November evening in 1979.

We walked back to the cottage and put in another hour before dinner. It's a fact that when I returned home to Westchester, New York that Christmas, my family stood aghast at the scrawny creature that greeted them. No one was more solicitous than Mari Michener when it came to caring for the welfare of her man, keeping the cottage squeaky clean, running errands for Jim, answering phones and fending off callers who could interrupt his writing. Michener had a heart attack twelve years earlier and Mari kept tabs on his health, making him take a nap each afternoon and watching his diet.

And there was the rub, for when Mari made meals for the three of us, she served her guest the same lean fare. The portions were beautifully presented, as one might expect from a hostess of American-Japanese heritage, but very small even for a thin man like myself. I was far too polite to ask for more, and besides, Mari had no real interest in cooking. It was fortuitous that one of Jim's close friends was Edward "The Big Fishcake" Piszek, owner of Mrs. Paul's Kitchens. Ed shipped boxes of frozen fish sticks to Broad Creek, as well as more exotic dishes from his test kitchens. Mari had a freezer stuffed with Mrs. Paul's largesse which she could've dispensed bountifully but stuck to her frugal meal plans. Packets of Heinz ketchup that Mari garnered from restaurants complemented Ed's fish sticks, a thriftiness that also kept their table supplied with mustard, soy sauce and a variety of sugars and sweeteners.

The three of us ate dinner in the kitchen, not much there to linger over but we passed the time pleasantly enough. Michener and I never spoke about work in Mari's company beyond scheduling issues, when he had to leave St. Michaels to fulfill other obligations. Some trips were to Cape Canaveral for he was already thinking of his next venture, which would be into space.

On days when Jim and Mari were both away, I was given the keys to a storage room and a freezer stuffed with frozen fish sticks and other provender. Mari kept the larder locked against long-fingered workers suspected of raiding her supplies. I was encouraged to take as much food as I wanted. Knowing how carefully my hostess portioned out her dishes, I gave myself the same sparse rations. Besides, if I got desperate, I could drive to a greasy spoon in St. Michaels. In 1979, the place was still a working watermen's town with a few upscale spots like Longfellows, not today's bivouac of boutiques and bistros where Washington warhorses make camp.

Alone in my quarters that November night, I returned to The Englishmen.

I heard a distant honking, as a flight of geese passed over Broad Creek and drove forward beneath the stars. The sound quickly faded far into the night. I waited expectantly for the coming and going of another flock of birds but there was only silence.

I was back beside Richard Saltwood, who helped the Xhosa in their national agony. In Michener's fictional story of The Englishmen, the major's aid to the stricken tribe brings him to the attention of Queen Victoria, who seeks his help with a settlement of Germans at the Cape, ex-mercenaries serving England in the Crimea. The major goes to London, where his royal commission makes him the darling of Punch magazine. He orchestrates the marriage of two hundred and forty legionnaires to brides scooped up in Portsmouth days before their ship sails for Africa. He lines them up on deck, men facing women, not a few of either sex listing to starboard. Starting at the top of each row, he pairs them off, for better, for worse, and sees them married on the spot. A Punch caricaturist strips Saltwood of his clothing, throws a diaper around his loins, and christens him "Cupid."

When Queen Victoria sends sixteen-year-old Alfred, the Sailor Prince, on the first royal visit to the Cape in 1860, Her Majesty asks Saltwood to keep an eye on Affie. The major escorts the prince on a grand battue that took place on a plain east of Bloemfontein. A thousand beaters drove tens of thousands of animals across the veld, black and blue wildebeest, Burchell's zebras, quaggas, ostriches, blesbok, hartebeest and springbok, herd after herd charging toward the guns of the prince's party. Six thousand animals died in the slaughter, the only regret for the huntsmen being Affie's failure to bag a single lion.

I had a special interest in the Great Hunt, for just over a century later I stood on the same plains in the Eastern Free State. I pictured the waves of rooigras sweeping across the veld and caught the thunder of galloping herds of game, an echo from the past that soon slid into the depths of my imagination. All I saw was the scarred earth with a canyon-like donga tearing through the desolation.

I was a reporter for Johannesburg Star and spent six weeks in 1966 crisscrossing a drought-ravaged South Africa for a feature series, which opened my eyes to the man-made denudation and climate change that changed the living veld into a creeping desert. Images I shared with Michener a decade later, not a simple before and after picture but a profound understanding of a fragile land.

For the fictional Saltwood, there was a final royal commission that would earn him a knighthood. It was this mission that kept me working until the small hours that November night, after scrapping Michener's ideas for the section and composing a totally new narrative.

In Michener's version, Saltwood traveled as Queen Victoria's goodwill ambassador to Mzilikazi in Matabeleland, part of the country known today as Zimbabwe. Saltwood's journey north of the Limpopo River did nothing to advance the story or foreshadow major developments in the book.

I chose instead to send Richard Saltwood back to British India where he served as a young man. He arrives at Madras eighteen months after the bloody Indian Mutiny. His commission is to contract laborers for the cane fields of Natal, a delicate negotiation in a crown colony still smoldering from the fires of insurrection.

"Saltwood was to hear endless stories of the Mutiny, and of the heroism of men, English and Indian, who had fought against the rebel regiments. He was furiously busy during his weeks in Madras, ironing out the hitches in the labor contracts, consulting with district officers and recruiting agents but he was able to accomplish all he set out to do and finally he stood in a great compound south of the town where 900 Indians squatted on the ground, all hoping to fill the 200 posts offered in the first ship to Natal. Within two hours the list was closed, but as Saltwood strode out of the compound the three Desai brothers arrived at the gates.

'Please, sahib, master, we go too.''You'll have to wait for the next ship.'...

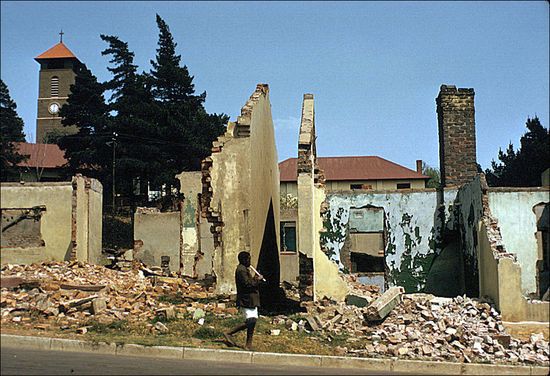

On the day the bulldozers move in, two Indians watch the destruction from a hill. Barney Patel and Peter Desai, later re-named "Woodrow" by Jim, live in nearby Pageview, a "Coolie location" granted to Indians seventy years earlier by President Paul Kruger of the Boer republic.

In showing how the Desais got to South Africa, I provided the ideal antecedent for Woodrow, grandson of one of the brothers, who came to work on the Natal cane fields. Woodrow's father moves to Johannesburg, where the family establishes a thriving grocery store and builds a fine house in Pageview. Woodrow is apprehensive as he witnesses the destruction of Sophiatown. He fears that the same blow will fall on the Indian community. He's right, for not long after this, Pageview's five thousand residents are ordered to pack up and move to Lenasia, a ghetto twenty-two miles away.

My Saltwood-Desai story appears here as I wrote it. Michener edited my words before he typed them up and pasted them into his manuscript. I kept my notes and drafts for the Desais, as well as other major writing I did for the novel. - The title came to me as I was compiling notes from our first planning session. - I held on to every scrap of paper in the sure knowledge that one day I would sit down and tell the story of my collaboration with Jim Michener on The Covenant.