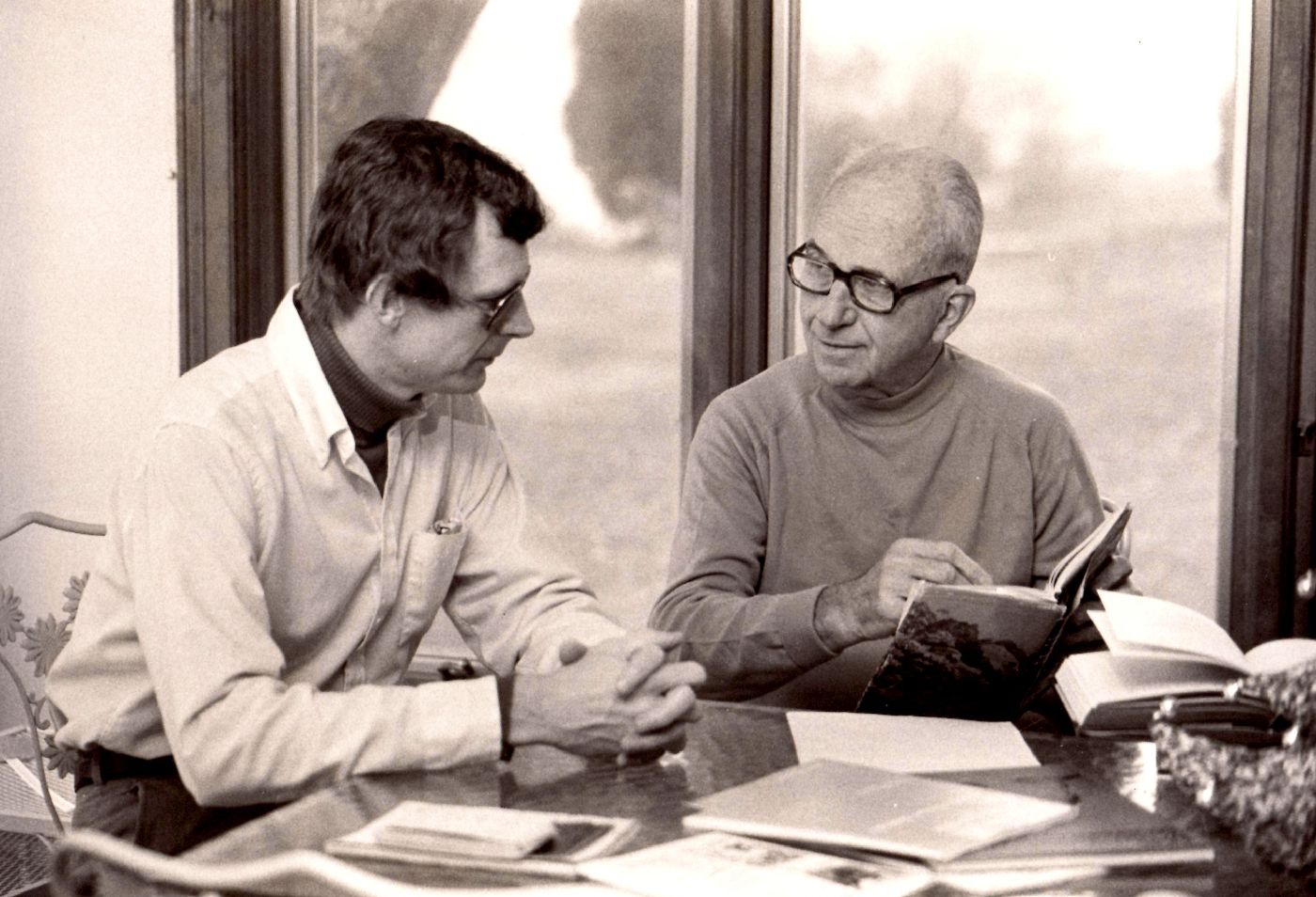

There was a shared sense of wonder at the circumstances that had brought us together, from continents apart but beginnings that were identical. Michener and I were both adopted as infants and knew nothing of our birth parents.

"I've never felt in a position to reject anybody," he once said. "I could be Jewish, part Negro, probably not Oriental but almost anything else. This has loomed large in my thoughts."

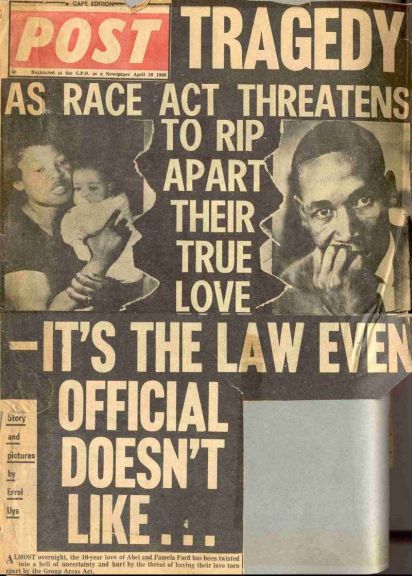

I had come to hold the same beliefs in my birthplace of South Africa, where so many were rejected for so long. My adoptive parents were from one of the oldest Afrikaner families of farmers and politicians, who believed apartheid was indeed a covenant with God.

When I disavowed such beliefs, I made myself an outsider. I am grateful I did, for otherwise I would never have found myself walking on the shores of the Chesapeake with James Michener.

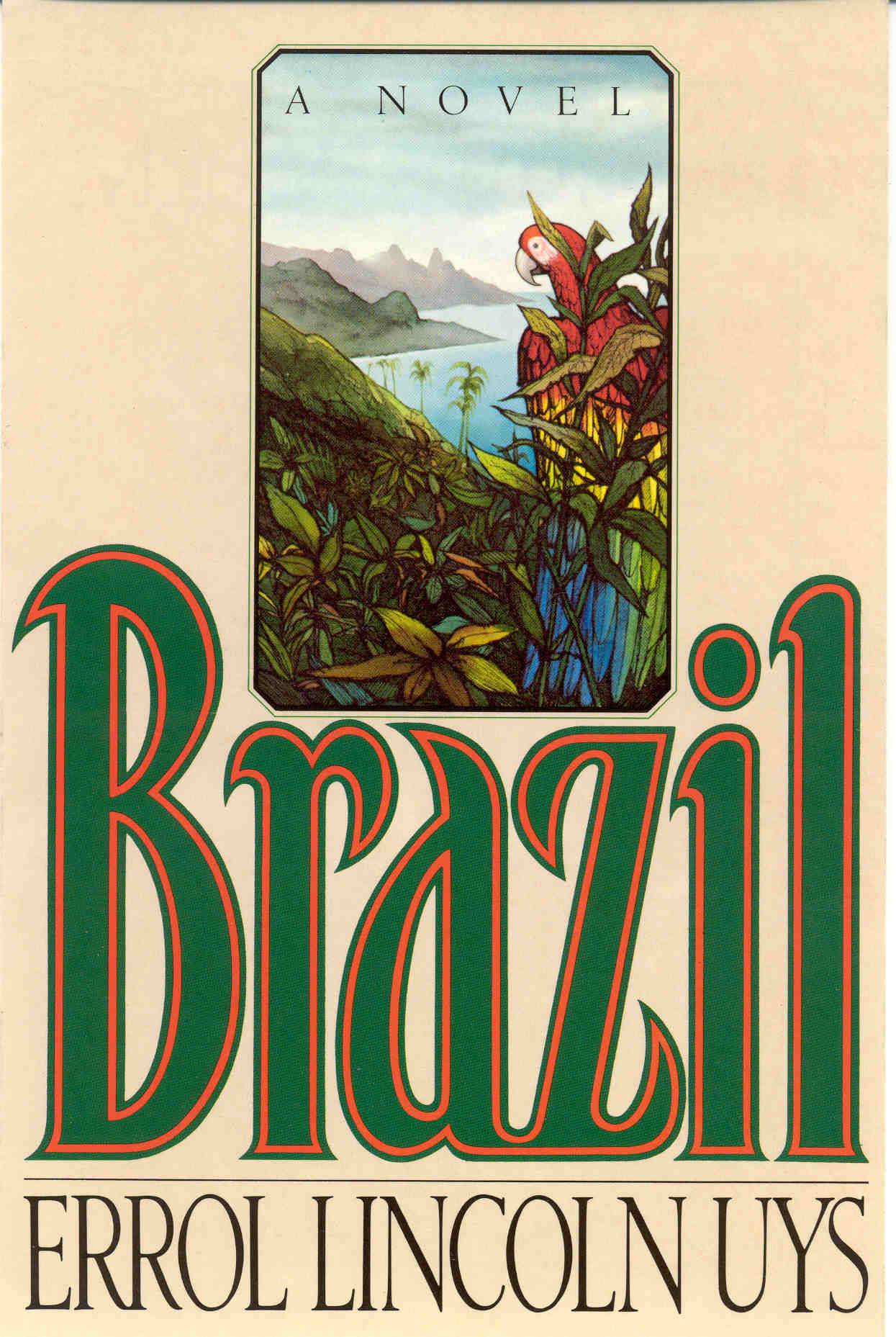

Michener awoke the magic of believing that I could go out and be a writer on a grand scale, with the same dedication to the great themes of history and understanding. While I was with Michener, we spoke of places that would lend themselves to treatment in big historical novels. He mentioned Texas and Alaska. I suggested Brazil.

When I quit the Digest to put my grand plan into action, Michener sent me an encouraging note:

"You unquestionably have the talent to write almost anything you direct your attention to. You're a great researcher and know how to put words together most skillfully. You have, from what I gleaned in our conversations on the long walks, an acute sense of timeliness in subject matter. That's a rare combination, the most promising I've met with in years of talking with would be writers."

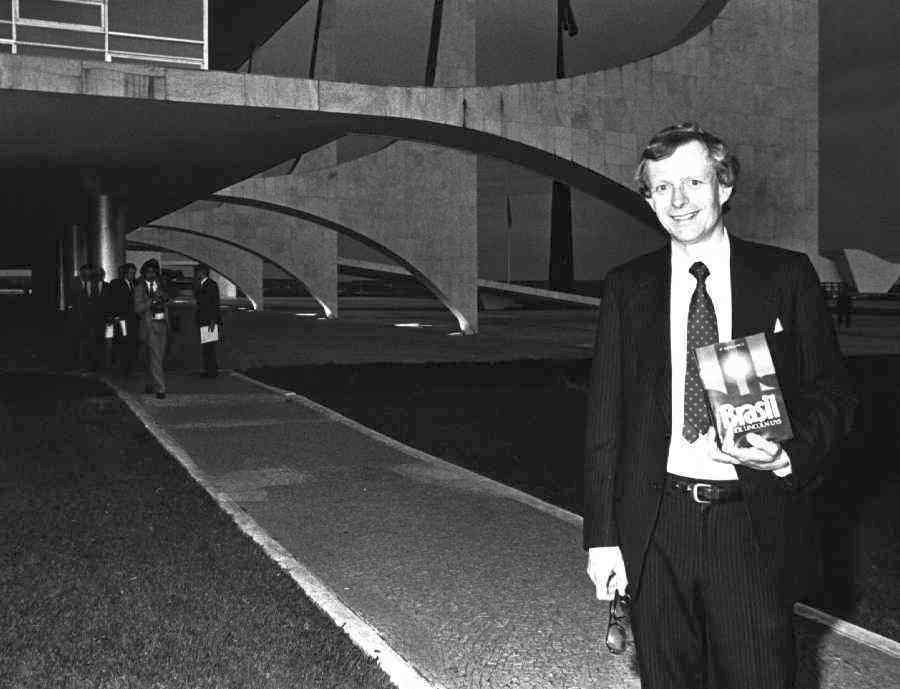

On the Road in Brazil

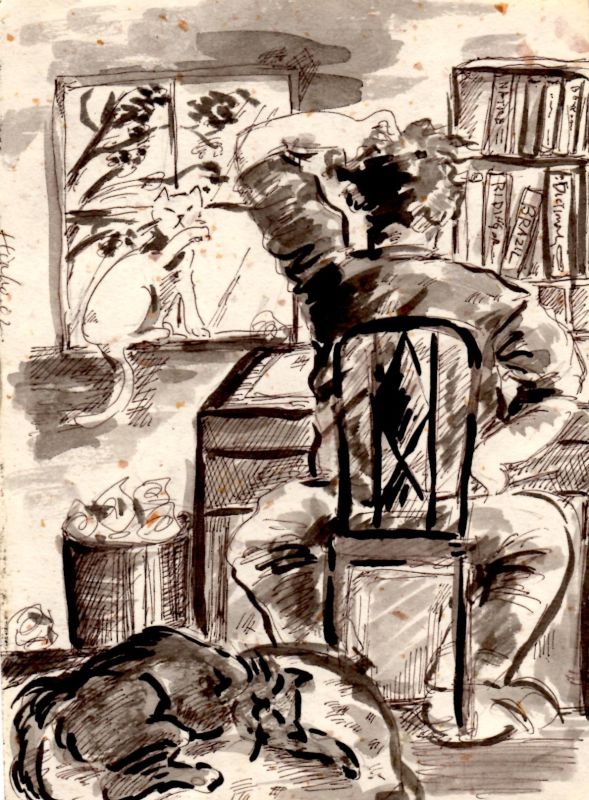

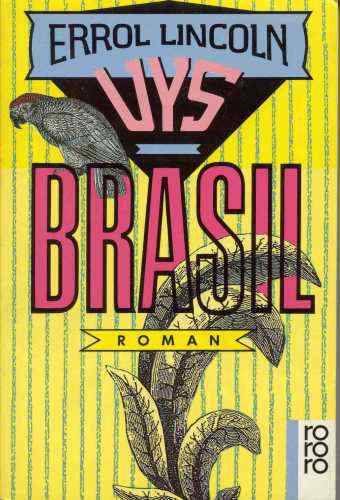

When I set out to research and write Brazil in January 1981, I knew little about the country. I haunted libraries and second hand bookstores in New York. I wasn't selective but read anything I came across concerning Brazil and Portugal, except fiction. This was something I learned from Michener, who avoided works of fiction related to his subjects to guard against unwittingly locking into the imagination of others.

At the end of three months, I had a 90-page outline for Brazil. I proposed a book spanning five centuries and involving multi-generations of two fictional families, the Cavalcantis and Da Silvas.

It was critical to have first-hand background knowledge. I could not go back 500 years in time but I could make a sincere attempt to know the land and understand the people. In April 1981, I pulled up roots and went to Portugal with my family; two months later I headed on alone to Brazil.

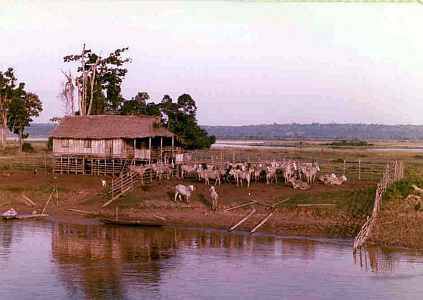

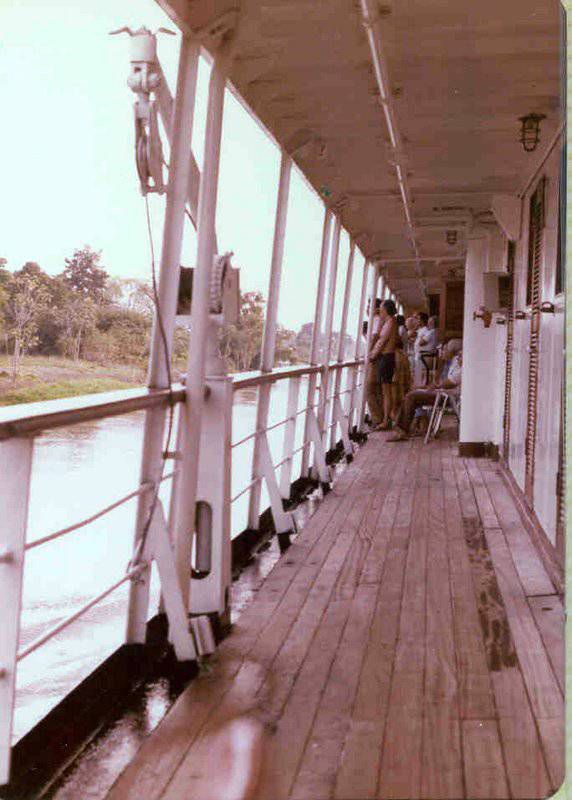

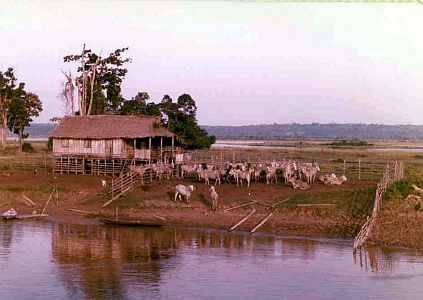

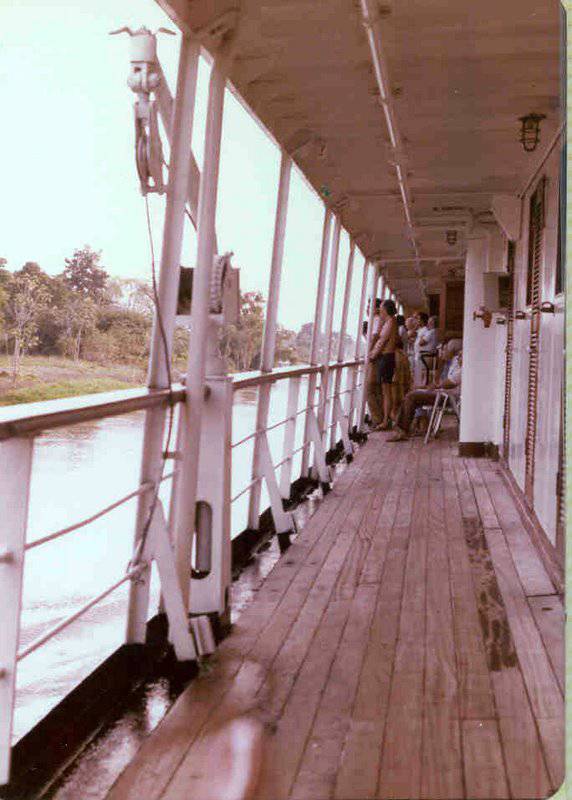

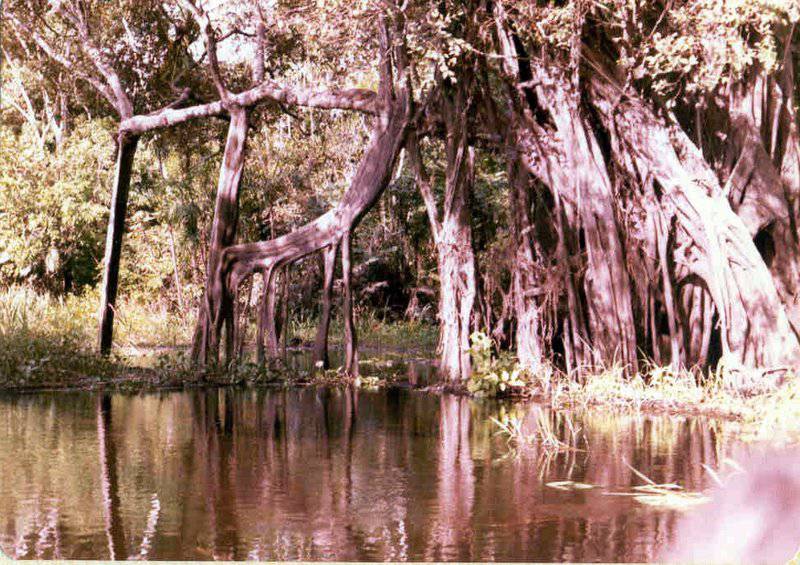

Over the next four months I traveled 15,000 miles, almost exclusively by bus to get a feel for that vast country at ground level. My journey took me into the sertão, the arid backlands of the North-East and to the Casas Grandes of coastal Pernambuco. I voyaged on the Amazon from Belem to Manaus and by bus down to southernmost Rondonia. I roamed the highlands of Minas Gerais and followed the route of the bandeirantes, the Brazilian pathfinders, west of São Paulo.